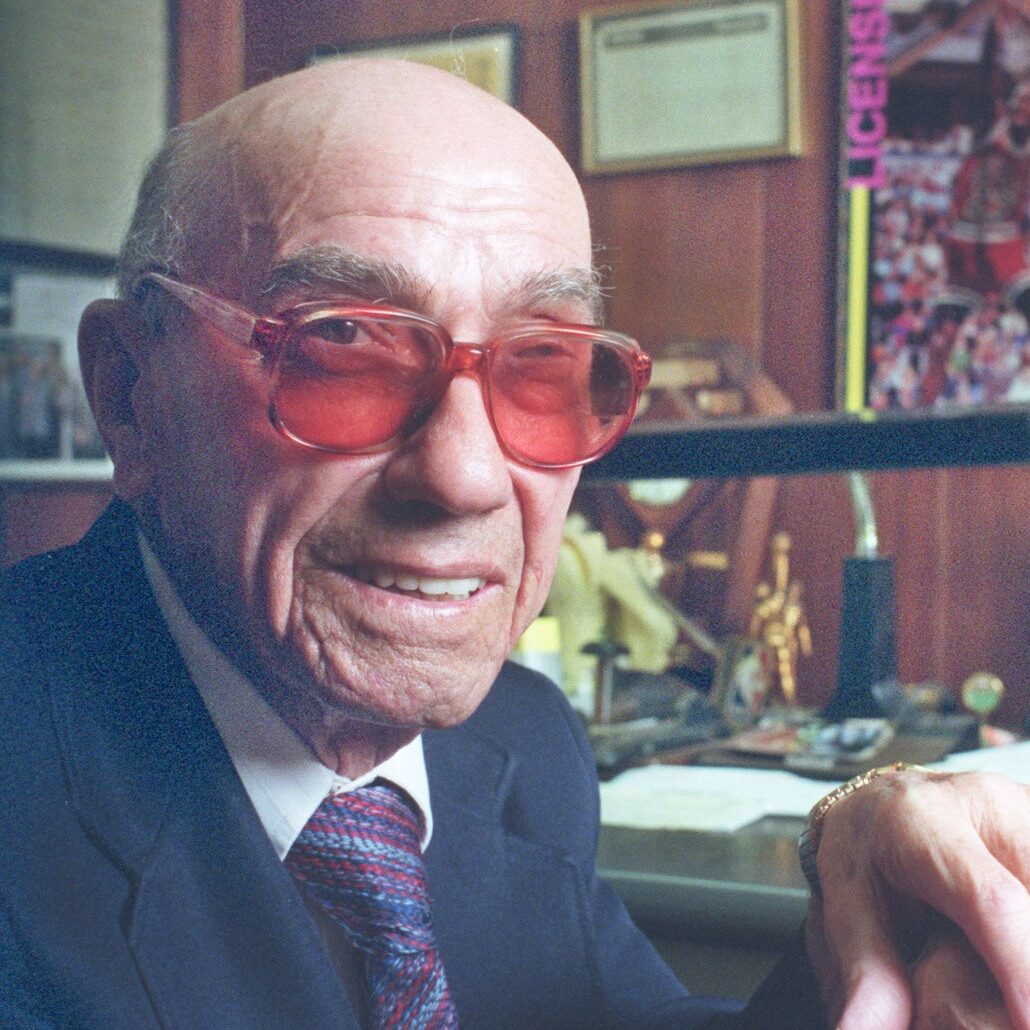

Dan Biasone

Basketball

Danny Biasone’s legacy in basketball is often measured by a simple, yet revolutionary, 24-second shot clock. As the founder and owner of the NBA’s Syracuse Nationals, Biasone introduced the shot clock in 1954, convincing NBA officials that it would speed up the game and make it more exciting. He based his idea on the premise that teams typically averaged 60 shots per game. By limiting the time to shoot, Biasone believed teams could still get the same number of shots, but in a faster-paced game.

The impact was immediate. Before the shot clock, NBA teams averaged 79.5 points per game. After its introduction, the average jumped to 93.1 points per game, and field goal attempts rose from 75.4 to 86.4 per game. This increase in scoring was not just a statistical improvement—it made the game more thrilling, drawing more fans and increasing the overall appeal of the NBA.

Biasone’s innovative idea helped set the stage for the NBA’s future success, revitalizing the game and boosting fan interest. A key figure in the early days of the league, Biasone owned the Syracuse Nationals from 1946 to 1963, leading them to an NBA championship in 1955. His introduction of the shot clock remains one of the most significant contributions to the sport.

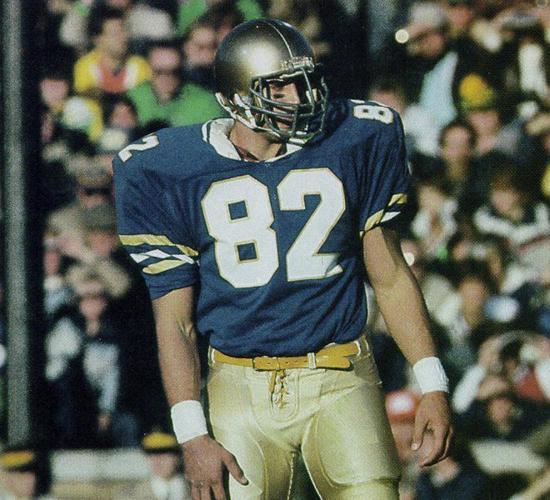

Mark Bavaro

Football

Mark Bavaro was a standout tight end in the NFL, known for his toughness, blocking ability, and clutch performances. Drafted by the New York Giants in the fourth round of the 1985 NFL Draft, Bavaro quickly made an impact as a rookie, finishing the season with 37 receptions for 511 yards and 4 touchdowns. He set a team record for most receptions in a single game and was named to the PFWA All-Rookie Team. Bavaro’s reputation as a physical and dependable player earned him the nickname “Rambo” and solidified his place as a key member of the Giants’ offense.

In 1986, Bavaro enjoyed a breakout year, setting a franchise record for tight end receptions with 66 catches, 1,001 yards, and 4 touchdowns. His tough play, including a memorable run against the San Francisco 49ers where he carried seven defenders, made him a fan favorite and earned him his first Pro Bowl selection. The following year, Bavaro again made the Pro Bowl after catching 55 passes for 867 yards and 8 touchdowns. His clutch performances helped the Giants win Super Bowl XXI in 1986, where he scored a crucial touchdown in their 39-20 victory over the Denver Broncos.

Bavaro’s career continued to flourish as the Giants reached another Super Bowl in 1990, where he made key receptions in Super Bowl XXV to help secure a 20-19 victory over the Buffalo Bills. Despite battling knee injuries in the later years of his career, Bavaro remained a valuable contributor to the Giants, earning a second Pro Bowl nod in 1987. However, injuries began to take their toll, and after a year on the physically unable to perform list in 1991, Bavaro played the 1992 season with the Cleveland Browns and the 1993 season with the Philadelphia Eagles.

Bavaro retired in 1995 after nine seasons in the NFL. Over his career, he amassed 351 receptions for 4,733 yards and 39 touchdowns. His contributions to the Giants were honored with an induction into the team’s Ring of Honor in 2011, and in 2022, he was named to the Professional Football Researchers Association’s Hall of Very Good. Known for his physicality and leadership, Bavaro remains one of the most memorable tight ends in NFL history.

Larry Brignolia

Running, Track

Born in April 1876 in Boston, Massachusetts, to Italian immigrant parents, Brignolia was the second of seven surviving children. His father worked as a street peddler, and the family lived in Cambridge. Brignolia attended St. Mary’s of the Annunciation school but left after sixth grade to apprentice as a horseshoer. By age 15, he was working in the trade independently.

Brignolia entered the inaugural Boston Marathon in 1897, finishing eighth with a time of 4:06:12, despite limited training and a large breakfast that led to cramps. In 1898, he improved dramatically, finishing fifth in the race with a time of 2:55:49, a 75-minute improvement over the previous year. In 1899, he took the lead in the marathon, battling a headwind and eventually winning the race with a time of 2:54:38, edging out Dick Grant by three minutes.

However, Brignolia’s attempt to defend his title in 1900 was unsuccessful. He suffered from a side stitch and dropped out after 11 miles, with Jack Caffery winning the race in a record time of 2:39:44.

In addition to running, Brignolia was an accomplished oarsman, winning races in rowing competitions such as the New England Amateur Rowing Association regatta. He was also a prominent figure in Cambridge, marrying twice—first to Nellie Eagan in 1899, with whom he had two children, one of whom tragically died young. Later, he married Annie Lynch in 1918.

Brignolia continued working as a horseshoer until the 1930s, when the trade began to decline. He lived in Cambridge until his death in February 1958 at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Boston following a car accident. He was around 300 pounds at the time. In 2000, Brignolia was posthumously inducted into the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame for his contributions to sports.

Dino Ciccarelli

Hockey

Dino Ciccarelli, born on February 8, 1960, in Sarnia, Ontario, was a standout player with the London Knights, where he became a junior hockey sensation. Over four seasons, he scored 72 goals and 142 points in his second year, and 50 goals and 103 points in his final season, earning the retirement of his number 8 by the Knights. Despite suffering a broken leg at age 16 and being considered too small for the NHL, Ciccarelli was signed as a free agent by the Minnesota North Stars in 1979. He made an immediate impact during the 1980-81 season, especially during the Stanley Cup playoffs, where he scored 14 goals and 21 points in 19 games.

In his first full season in the NHL, Ciccarelli scored a career-high 106 points, including 55 goals. Known for his gritty, in-your-face playing style, he became a consistent goal-scorer, often netting goals from in front of the crease while absorbing punishment from defenders. After nine successful seasons with the North Stars, Ciccarelli was traded to the Washington Capitals in 1989, where he continued to score but was part of a team that struggled in the playoffs, leading to a move in 1992 to the Detroit Red Wings.

With Detroit, Ciccarelli thrived, scoring 41 goals and 97 points in his first season. He helped the Red Wings reach the Stanley Cup Final in 1995, although they were defeated by the New Jersey Devils. In the following seasons, Detroit finished first overall in the league in 1995 and 1996. After the 1996 season, Ciccarelli was traded to the Tampa Bay Lightning, where he enjoyed a resurgence, scoring 35 goals and 60 points in his one season with the team. Despite his individual success, the Lightning struggled in the standings, and Ciccarelli was traded to the Florida Panthers in 1998.

Ciccarelli achieved a career milestone with his 600th NHL goal while playing for the Panthers, but his 1998-99 season was marred by a back injury that limited him to just 14 games. He retired in 1999 after 1,232 NHL games, with 608 goals, 592 assists, and 1,200 points. Known for his physical play and goal-scoring ability, Ciccarelli was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2010. Despite never being drafted, his remarkable career established him as one of the NHL’s top goal-scorers and a player whose tenacity and grit left a lasting legacy.

Eleanor Garatti

Swimming

Eleanor Garatti-Saville was one of the United States’ premier female sprinters in the late 1920s and early 1930s. She won gold in the 400m freestyle relay at both the 1928 Amsterdam and 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. In addition, she earned a bronze medal in the 100m freestyle at the 1932 Games, narrowly finishing behind her teammate, gold medalist Helene Madison, and Holland’s silver medalist, Willy den Ouden. Garatti-Saville is one of only two women in history, alongside Australia’s Dawn Fraser, to medal in the 100m freestyle in two consecutive Olympic Games.

Between the 1928 and 1932 Olympics, Eleanor married, but she continued her swimming career at a time when women were often expected to prioritize domestic roles. Beyond her individual success, she was a key member of the U.S. 400m freestyle relay teams, which won gold in both Olympic Games she participated in.

Garatti-Saville also dominated at the national level, winning four U.S. National Sprint Championships from 1925 to 1929. Her contributions to American swimming, particularly in relay events, helped solidify her legacy as one of the sport’s greats during her era.

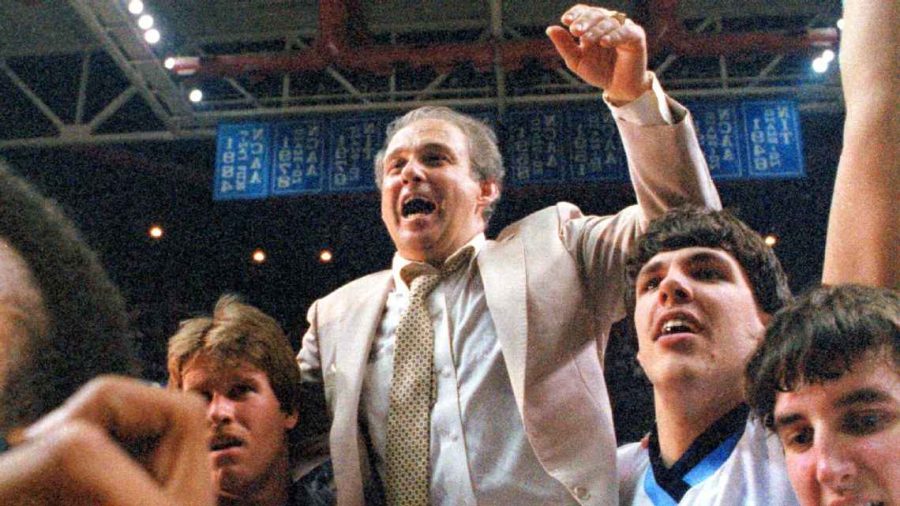

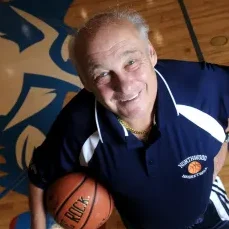

Roland “Rollie” Massimino

Basketball

Rollie Massimino, a legendary college basketball coach, is best known for leading the Villanova Wildcats to the 1985 NCAA Championship. In 2006, he helped establish the Northwood University basketball program, where he led the Seahawks to nine National Tournament appearances, including two Final Fours. Massimino’s leadership brought the Seahawks seven Sun Conference Regular Season Championships and two Tournament Championships.

In 2016, Massimino joined the exclusive 800-win club with his 77-47 victory over Trinity Baptist. He was named NAIA National Coach of the Year in 2011 and Rawlings National Coach of the Year in 2012. Within the Sun Conference, he earned Coach of the Year honors five times, including in the 2015-16 season.

Massimino was inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame in 2013 and was a finalist for the Naismith Hall of Fame in 2017. Notably, in 2012, he became only the third coach in history to reach 700 career wins and win an NCAA Championship.

Before his time at Northwood, Massimino enjoyed a storied career at Villanova. Under his guidance, the Wildcats made 16 postseason tournament appearances, with 11 NCAA Tournament berths. He earned multiple coaching accolades, including National Coach of the Year honors in 1985. His Villanova teams won two Big East titles and consistently performed at a high level, including a 110-80 regular-season record in Big East play.

Massimino’s coaching philosophy, known as “Family Style,” emphasized enthusiasm and energy. His infectious passion for basketball and life inspired his players to give their best both on and off the court.

Massimino began his coaching career in 1956, after playing at the University of Vermont. He started as an assistant coach at Cranford High School in New Jersey before moving on to head coaching roles at Hillside and Lexington High Schools, where he won a state championship. He transitioned to college basketball in 1969 as head coach at SUNY-Stony Brook, and later became an assistant at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1973, he took over as head coach at Villanova, where his coaching legacy truly flourished.

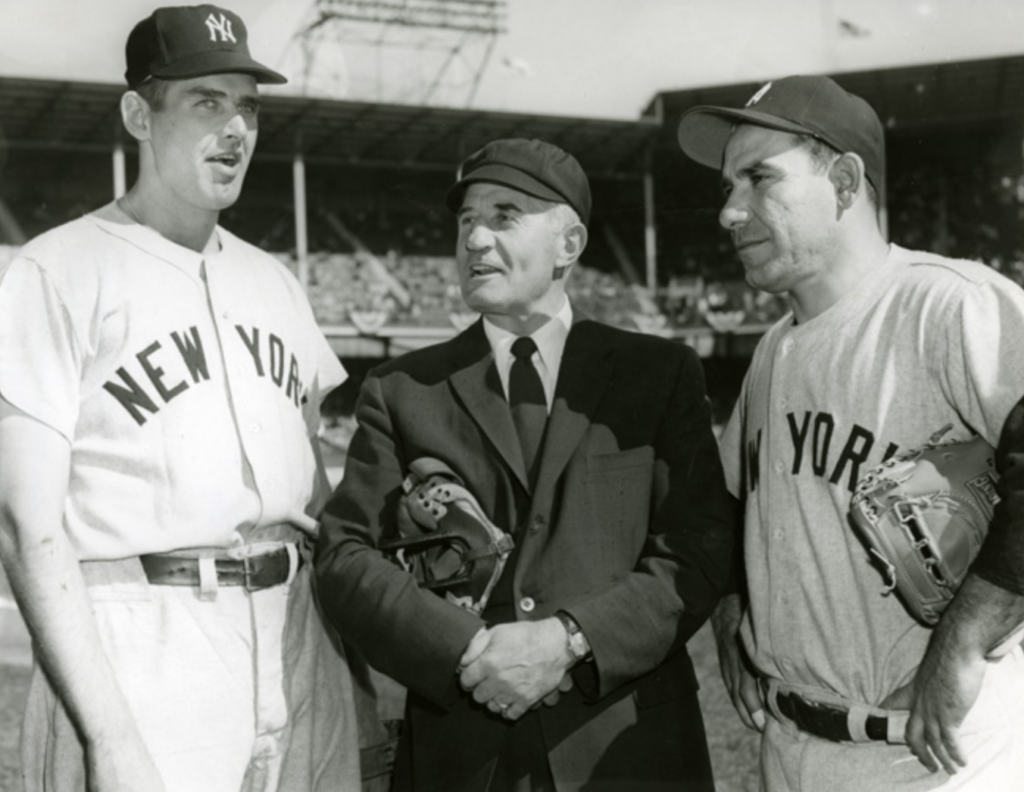

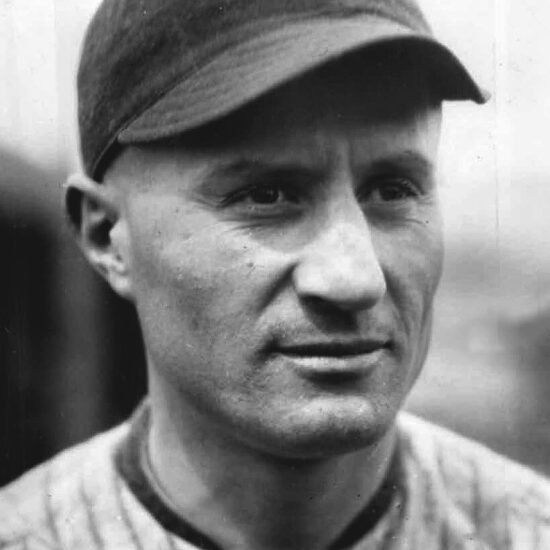

Babe Pinelli

Baseball, Umpire

Babe Pinelli, best known for his significant contributions as both a player and umpire, became a baseball icon through his remarkable career in the major leagues. Most notably, Pinelli was the umpire behind the plate for Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series, a historic moment that remains the only perfect game in World Series history. His call of a third strike on Dale Mitchell to end the game is considered one of the defining moments of his career, and despite some criticism of the call, Pinelli firmly stood by his decision, noting Larsen’s exceptional control. The game marked the apex of his 22-year career as a National League umpire, after which Pinelli retired, feeling that nothing could top the historic game he had just officiated.

Before his umpiring success, Pinelli had a fiery playing career. Born Rinaldo Angelo Paolinelli in San Francisco in 1895, he rose from humble beginnings to play professional baseball, starting in semipro leagues before moving to the Pacific Coast League. A versatile infielder, Pinelli played for several teams, including the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers, showcasing his combative, hard-nosed playing style. He was known for his fiery temper and frequent altercations, both with opponents and teammates. Despite his gritty playing style, his major league career was short, with his most successful seasons coming with the Cincinnati Reds in the early 1920s, where he hit .306 in 1924 and was among the league leaders in putouts and assists.

Pinelli’s playing days were cut short due to declining performance, and by 1927, he shifted his focus to umpiring. His transition was aided by the encouragement of former teammates and umpires, including Bill Klem, and after a brief stint in the Pacific Coast League, he was hired by the National League in 1935. Pinelli quickly earned a reputation as a calm, competent umpire, earning the nickname “The Soft Thumb” for his reluctance to eject players. He worked four World Series, four All-Star Games, and umpired many historic moments in baseball, including Jackie Robinson’s barrier-breaking game in 1947 and the first night games in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. Known for his diplomatic approach, Pinelli’s ability to manage difficult situations on the field, such as dealing with the fiery Leo Durocher, made him one of the most respected umpires of his era.

Pinelli’s impact on baseball extended far beyond his umpiring skills. He officiated more than 3,400 games over 22 seasons, earning praise for his even-handedness and self-control. Despite his rough start as a player, he became a respected figure in the game, with his 22 years of umpiring marking the second-longest tenure of any major league umpire at the time. He retired in 1956 and later worked as a scout for the Cincinnati Reds. Reflecting on his career, Pinelli considered umpiring to be the best job in baseball, as it provided a stress-free role compared to the pressures of playing. He passed on his wisdom to future generations, leaving behind a legacy as one of the greatest umpires in the history of the sport.

Lindy Remigino

Track and Field

Lindy Remigino was a standout track and field athlete, earning national fame with two Olympic Gold Medals. At the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, he claimed gold in the 100-meter dash with a time of 10.4 seconds, narrowly defeating Jamaica’s Herb McKenley in a race where the top four finishers were all clocked at the same time. Later in the 4×100-meter relay, Remigino ran the third leg to help the U.S. team secure another gold medal. His Olympic success paved the way for his induction into several prestigious halls of fame, including the USA Track & Field Hall of Fame, the New York Athletic Club Hall of Fame, and the New York Armory Track Center Hall of Fame.

During his college career at Manhattan College, Remigino earned All-American honors with a fifth-place finish in the 100-meter dash at the 1952 NCAA Outdoor Championships. He also won three EC4A championships in the 100-meter, 200-meter, and 220-yard races. After graduation, Remigino remained undefeated in the 100 meters in post-Olympic European track meets, solidifying his reputation as one of the world’s top sprinters.

After his competitive career, Remigino transitioned to teaching and coaching, becoming a physical education teacher and track coach at Hartford Public High School, his alma mater. As a coach, he achieved remarkable success, leading his teams to 31 state titles and guiding 157 athletes to individual state championships. His contributions to the sport extended beyond his personal achievements, as he played a key role in developing the next generation of track and field talent.

Remigino’s legacy is one of excellence both on and off the track. His Olympic success, combined with his coaching accomplishments, cemented his place as one of the most respected figures in American track and field history. His induction into multiple halls of fame honors not only his athletic prowess but also his lifelong dedication to the sport.

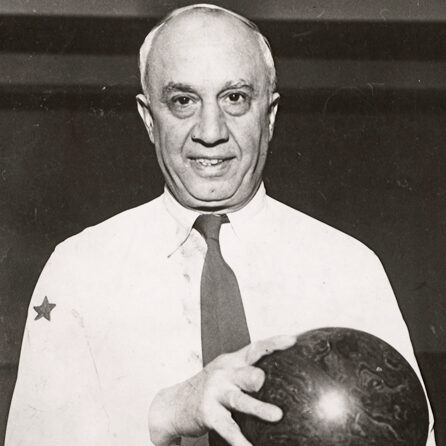

Jimmy Smith

Bowling

Jimmy Smith was primarily known as an exhibition bowler, though he achieved notable success in competitive events, winning two USBC Open Championships All-Events titles. He was also selected for the prestigious Bowling Magazine Pre-1950 All-America First Team. Smith twice triumphed in the renowned Petersen Classic in Chicago, solidifying his reputation in the bowling world. In 1928, he gained further recognition in one of the few arranged matches of his career, defeating the legendary John “Count” Gengler and effectively sending the famed hustler into retirement.